Surveying the Bird Community at a National Wildlife Refuge with Passive Acoustic Monitoring

Gathering Baseline Avian Community Data Ahead of Major Wetland Restoration at John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge.

- Overview

- Background

- The Restoration Proposal

- Survey Design

- Automated Detection and Data Processing

- Conclusion

Overview

Nestled within the urban expanse of southeastern Pennsylvania’s Philadelphia and Delaware Counties lies the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge (JHNWR)–a beautifully preserved expanse of wetlands and woodlands that form a refuge for people and animals alike. A portion of the refuge called the Henderson Marsh, which has already seen numerous restoration interventions in the past, is scheduled to recieve yet another–a major project that will breach a dyke in attempts to restore healthy, natural hydrology to the area. This wildlife refuge currently boasts nearly 300 acres of Pennsylvania’s few remaining freshwater tidal marshes, providing critical habitat for a wide array of species of conservation concern within the region, and has been designated as an important bird area by the National Audubon Society.

Ahead of this project, refuge scientists wanted to gather data about the avian community that could serve as a baseline against which the results from future surveys could be compared. There was a special interest in cryptic marsh birds like the Virginia rail, least bittern, sora, and King rail. A colleage and I proposed passive acoustic monitoring (PAM) as an efficient and highly effective way to gather this baseline data. PAM would allow for continuous monitoring across the entire area of interest, produce a dataset that was easily processed by two researchers, and would allow for the establishment of easily replicable protocols so that future comparisons could hold more weight.

Background

The refuge sits barely above sea level, resulting in a daily tidal fluctuation of approximately six feet. However, throughout its history, the land on which the refuge is located has seen numerous significant changes that have altered its landscape and its hydrology. European settlers first erected dikes for agricultural purposes in the Tinicum marshes as early as the 17th century. More recently, from the 1950s to the 1970s, an area known as Henderson Marsh, which encompasses roughly 150 acres on the Delaware County side of the refuge, was the site of dredge disposal by the Army Corps of Engineers (USFWS, 2012). Both the dredge disposal and the creation of dikes altered the site’s natural hydrology by hindering tidal connectivity and thus changing the Henderson Marsh ecosystem.

The Restoration Proposal

According to the Henderson Marsh Restoration Project grant proposal, this will be achieved through the excavation of 13,073 linear feet of tidal channels, and the breaching of a new opening in the dike that currently separates Henderson Marsh from Darby Creek. The resulting seven acres of channels and pools will allow for the flow of native plants into the wetland interior and improve the marsh’s overall ecosystem function.

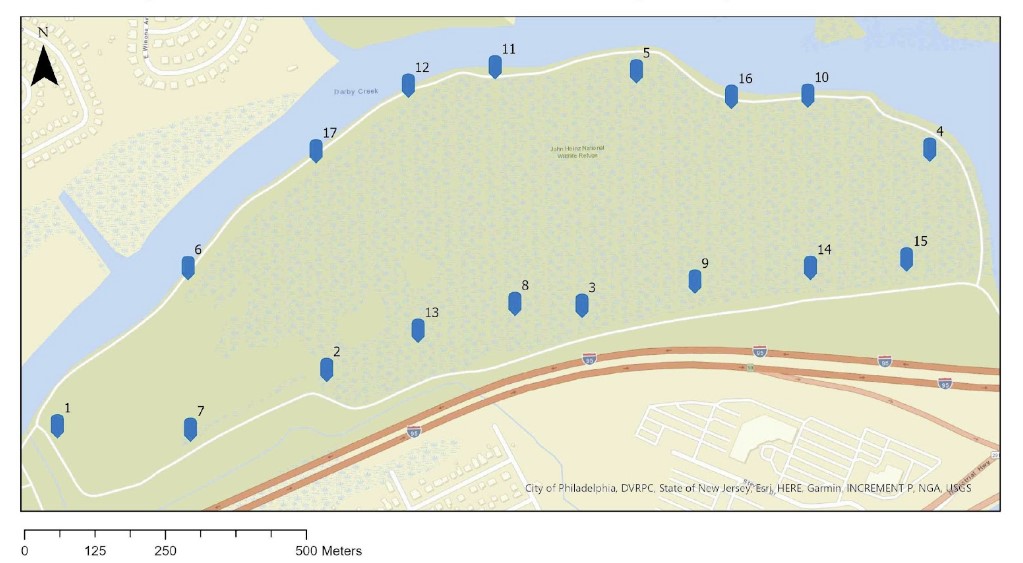

Survey Design

Recording sites were originally sampled randomly from the entire marsh area, but most of these points were impossible to access because of large tidal fluctuations and a lack of available watercraft to efficiently navigate the channels. Instead, points were evenly distributed around the marsh’s edge, making them all accessible by foot with small excursions off the trail. Seventeen sites were selected in this way.

Recordings took place in five two-week deployments, meaning that not all 17 sites were surveyed simultaneously. During this two-week period, six recorders were installed and evenly spaced around the marsh to avoid clustering and biasing specific marsh areas during any given deployment. After two weeks, the recorders were collected, and new recorders were installed at new sites.

Automated Detection and Data Processing

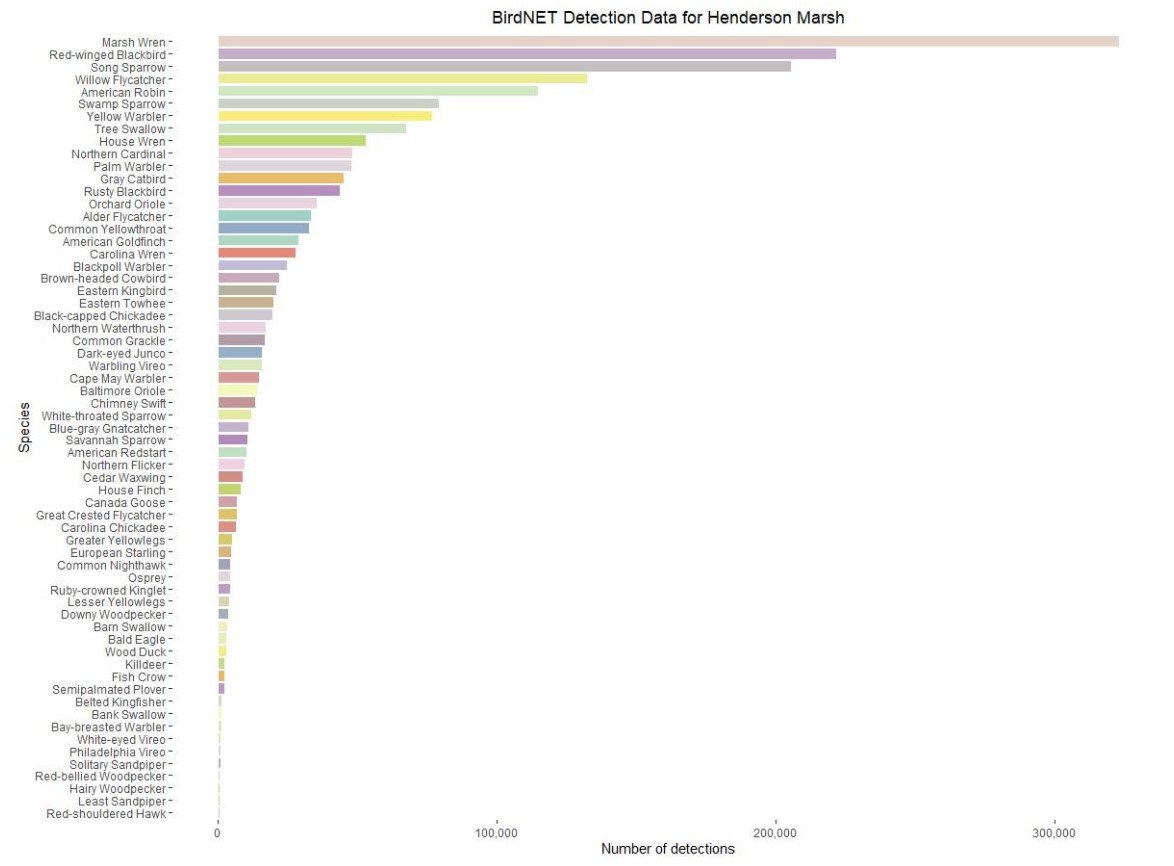

Our primary detection model was BirdNET–a publicly available model from Cornell University that can identify well over a thousand species of bird. Because BirdNET does not always perform well with cryptic marsh birds, we also employed a custom-trained convolutional neural network called RailNET.

Cryptic Marsh Birds

For these special targets, we manually reviewed a large portion of the detection data. Models searching for rare signals like these tend to produce a lot of false positives because of issues like class imbalance and integrity issues with training data. Well over 90% of results from the detection model were false positives. While this seems like horrible performance, it still takes the entire dataset of thousands of hours of raw audio and cuts it down to a manageable size for manual review–narrowing down the search for the needles in the haystack significantly.

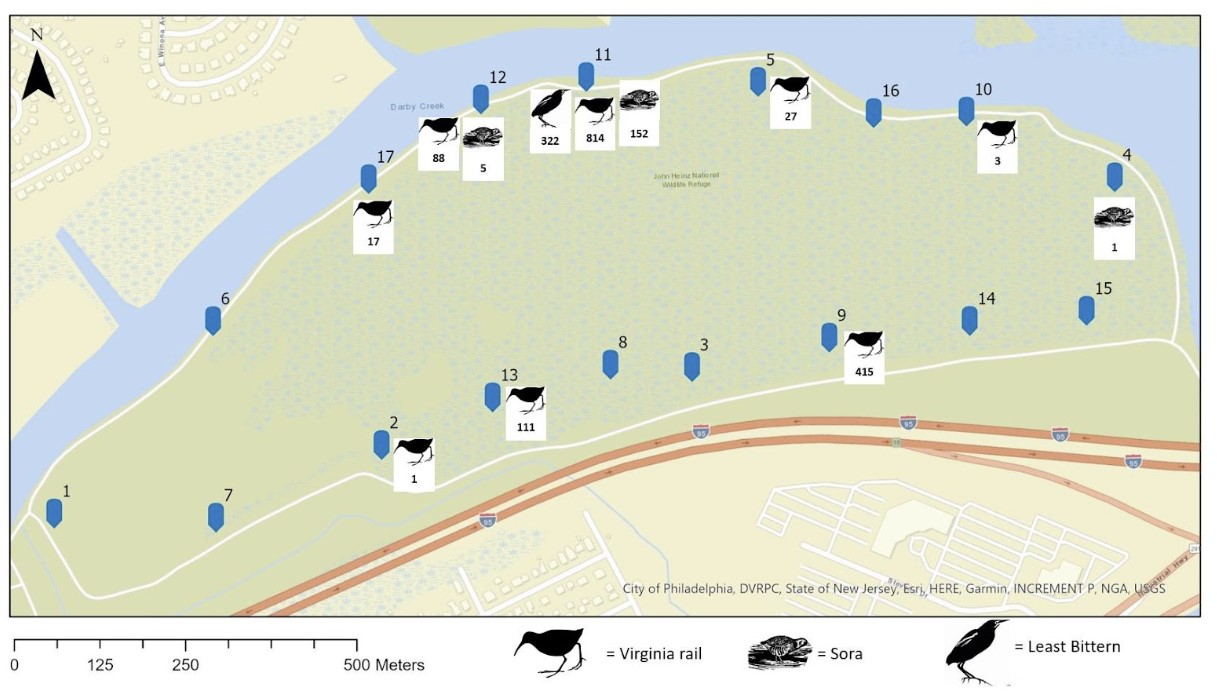

We reviewed rouhgly 35,000 acoustic signals during this stage of the process–discovering 1,476 Virginia Rail vocalizations, 322 Least Bittern vocalizations, and 158 Sora vocalizations. The distribution of these detections across the study area is visualized below.

Full Bird Community

Since the focus of this project was on the cryptic marsh birds, we did not manually validate detection data for the full bird community. However, an efficient and systematic approach could easily be implemented to do just that–such as validating a subset of detections for each species or validating the presence of each species at each site. For the purposes of this project, we defined an algorithmic cutoff making use of the confidence scores that BirdNET assigns each detection. Our final bird list contained birds that were detected more than 15 times and whose top 15 detections (ranked by confidence score), averaged to greater than 0.7. This eliminated birds with only a handful of high confidence detections.

Conclusion

Overall, this was a highly successful survey. We established a solid, basleine idea of what cryptic marsh birds are using the marsh and which parts of the marsh they are using. In addition to this, we have an easily replicable protocol that will allow future surveys to compare metrics like species richness against our own data as a baseline. What’s more, the audio we collected is archived, labelled, and can serve as a rich dataset for further investigation–starting with a more careful look at detection data from the whole avian community.