RailNET - A Convolutional Neural Network for Acoustic Monitoring of Elusive Species

Using Deep Learning to listen for elusive species like the Virginia rail.

Overview

RailNET is an ensemble of Convolutional Neural Networks that specializes in a single bird: the Virginia rail. Rails are cryptic marsh birds–meaning that they are exceedingly difficult to find with your eyes. Being secretive and difficult to detect means that monitoring programs often struggle to gather data about population trends. Because their signals are rare and sporadic, and because one needs to detect these scattered signals from within an audio dataset that is overwhelmingly comprised of sounds that are not from the target species, exploring means for improving model performance in this use-case would be generalizable to other scenarios where massive class imbalance in the real-world data is unavoidable.

Model Development

Why?

I developed RailNET because after joining an effort to study these birds using Passive Acoustic Monitoring on a large wetland preserve, I found that the existing state-of-the-art model for avian monitoring, BirdNET, was not performing as well as expected with the Virginia rail–spitting out thousands of false detections and missing a number of vocalizations I knew to be present. The precision of the model was hovering around just 1%.

Sifting through a mountain of false positives in order to identify the true positives requires a lot of manual validation effort, so even small gains in model precision could drastically cut down on the hours required to process the data.

Hypotheses

Before training, I had a few hypotheses for how I might improve upon BirdNET’s performance–both model- and data-centric.

On the model side…

A specialist, binary-classsifer, might perform better on a specific species than a multi-class model trained to recognize over 1,000, many of which are not relevant to the survey at hand.

By ensembling multiple, separately trained ResNets, I could mitigate the impact of any single model’s sometimes erratic predictions, potentially seeing a drop in false positives.

On the data side…

- BirdNET was trained on publicly available data that is weakly labeled (i.e. the whole recordings have a species label, but no timestamps indicating vocalizations). Since recordings are sure to be full of other species vocalizing, there is a high risk of training data for a certain class being polluted with vocalizations from another class. With automated methods to chop up recordings into training data samples, it is likely that the most prominent vocalizers in the avian community are the heaviest polluters and that infrequent vocalizers like rails may often not even be the stars of their own recordings. By strongly labelling data for the Virginia rail (i.e. manually curating a class that only contains Virginia rail vocalizations), it is likely that performance will improve. This problem is illustrated in the picture below.

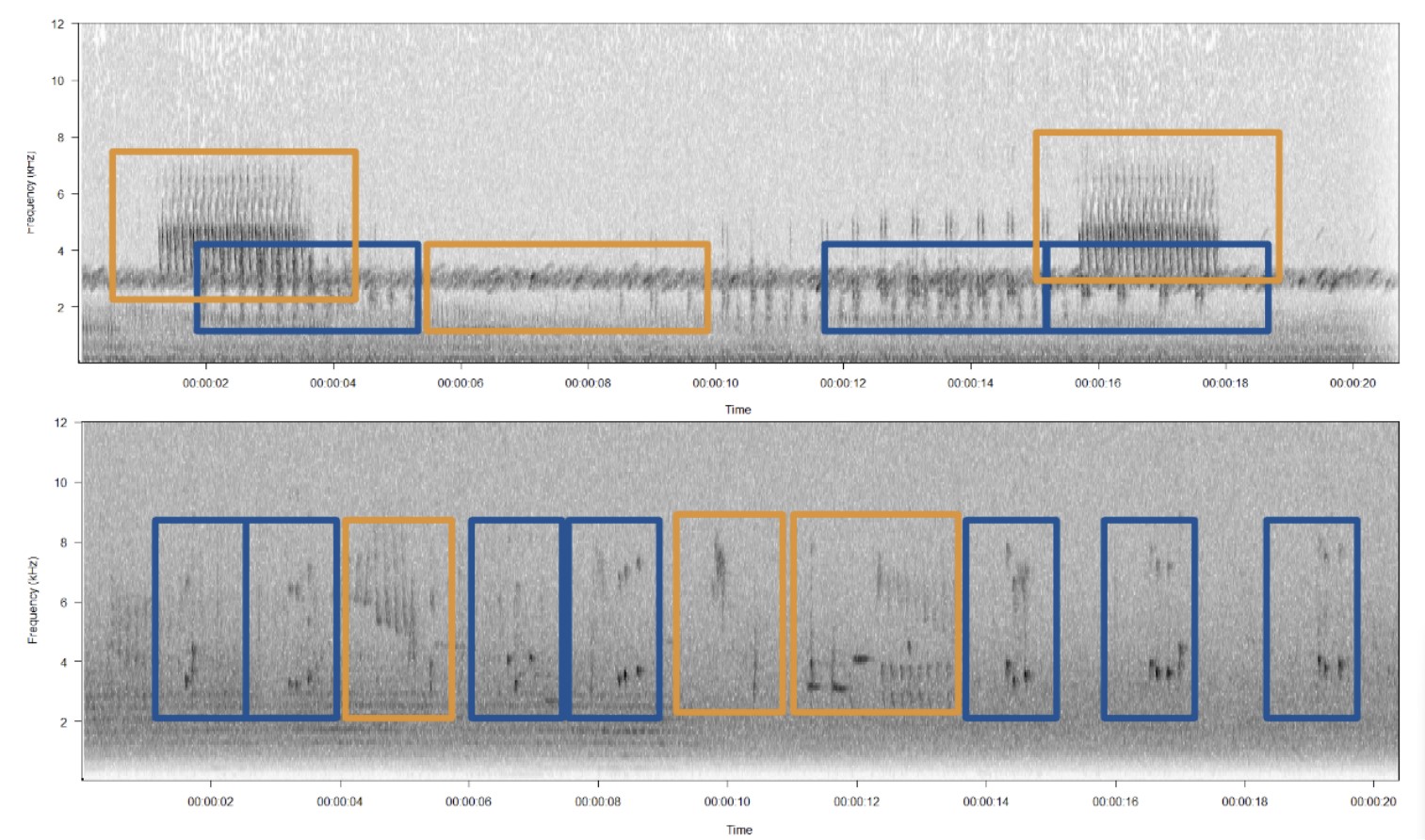

This figure depicts two audio segments from a recording labelled in a public database as containing Virginia rail vocalizations, and illustrates the data integrity issue where multiple species can easily come to pollute training data for a certain class. The navy blue boxes indicate true rail vocalizations, and the organge boxes indicate the vocalizations of other species. In an automated, amplitude-based data curation process, these other species would be included in the training data for the Virginia rail.

This figure depicts two audio segments from a recording labelled in a public database as containing Virginia rail vocalizations, and illustrates the data integrity issue where multiple species can easily come to pollute training data for a certain class. The navy blue boxes indicate true rail vocalizations, and the organge boxes indicate the vocalizations of other species. In an automated, amplitude-based data curation process, these other species would be included in the training data for the Virginia rail.

- By excluding irrelevant species in training and focusing on species that are the most vocally gregarious, the model will be able to devote its full capacity to distinguishing between the Virginia rail’s vocalizations and the most likely background sounds.

Model building and training

I built the models in Python using the PyTorch framework. Since BirdNET was based on a ResNet architecture, I prioritized experiments with ResNets of various depths. However, for comparison, I also tested a VGGish architecture and a simpler, vanilla CNN with only a few layers. In addition to these deep learning benchmarks, I tested a traditional machine learning Support Vector Machine.

The generalization problem

A common problem with machine learning models is a sometimes huge discrepancy between how they perform during training and how they perform in the real world. With deep learning models, which have milliones of parameters that update during training, it is very easy to overfit to the training data, which essentially means that they can memorize the training data and find a solution that is optimal for that dataset but that does not generalize well to the distribution of data they will encounter ‘in the wild’.

Bioacoustic monitoring applications suffer from this as well, with many papers citing a massive drop in performance when shifting from training/validation to real-worl deployment. Ideally, the distribution represented by the training data would the same as the distribution represented by the real world data the model will eventually encounter. With acoustic wildlife monitoring, however, the trianing databases are largely comprised of higher-quality, focal recordings that are uploaded by users around the world precisely because they are good specimens. On the one hand, this is good, because the model will be able to develop a sound understanding of what each class is like. On the other hand, though, the model is going to be ingesting unfocused soundscape recordings, where a vast majority of the segments it attempts to classify are rife with mixed, unknown signals and background noise.

One way to combat this would be to curate data that better reflects reality, which is not usually a feasible option. So, you then have to transform what data you have in ways that better simulates the expected distribution. This can be done through data augmentation.

Data augmentation

Data augmentation involves transforming your data as you train your model–effectively increasing the size of your dataset by showing your model the same samples with various transformations. This is a very important step in addressing the generalization problem. There are a variety of data augmentation techniques that are common to audio classifcation and that I used when training RailNET:

- Frequency masking: randomly blocking out certain frequency bands (horizontal bands) of the spectrogram.

- Time masking: randombly blocking out certain time steps (vertical bands) of the spectrogram.

- Horizontal translations: random horizontal shifts of the spectrogram. With other image classifcation tasks, you can shift vertically and perform rotations, but the nature of spectrograms is that any translation impacting the vertical axis would essentially change the frequency/pitch and the nature of the sound. Therefore, only horizontal shifting is realistic, simply simulating the acoustic signal occuring at different time steps within the frame.

In addition to these common data augmentation techniques, I wanted to create intentional, directed transformations that would help simulate real world conditions:

- Adding random gaussian noise: ambient sound from wind, rain, cars, etc. can really distrub audio recordings. By injecting random levels of gaussian noise into training samples, I hoped to mimic faint signals.

- Adding true soundscape noise: using ‘scraps’ from training data, I overlaid data samples with actual recording segments from ecological soundcapes. This mimics the very realistic assumption that many animals will be vocalizing at once, and the target signal might be obscured by multiple competing sounds.

To see specific examples of this in action, you can read my blog post, The Importance of Data Augmentation in Passive Acoustic Monitoring.

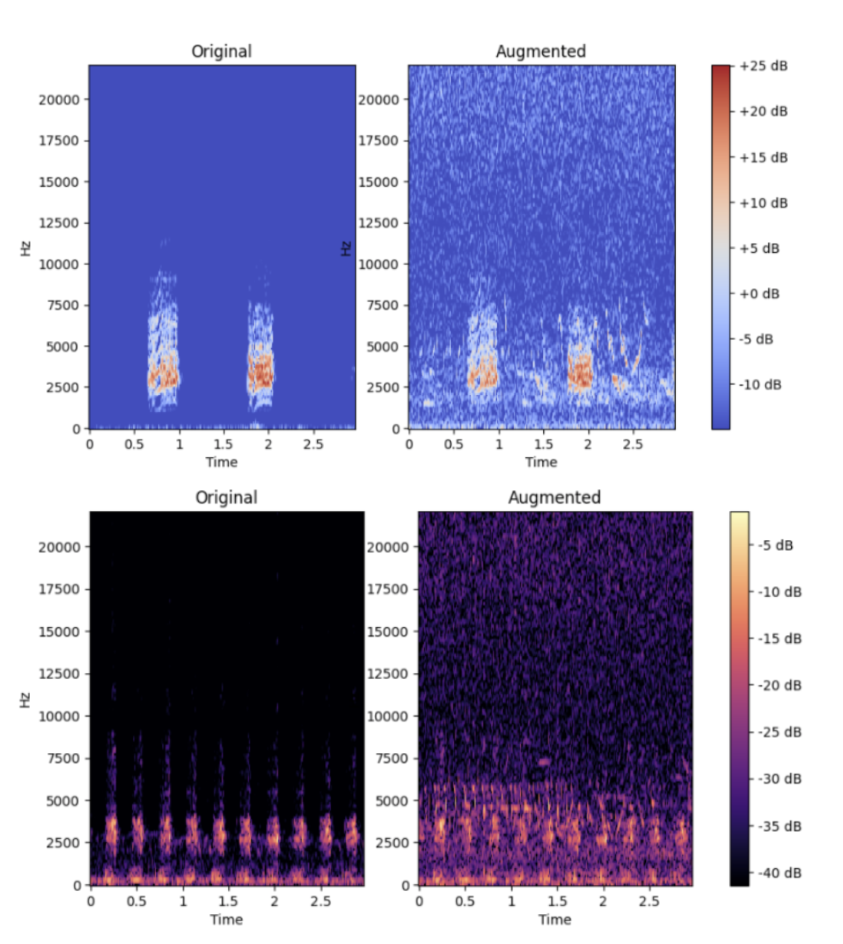

This figure shows two audio samples from the training set before (left) and after (right) they were overlaid with soundscape audio, creating a much more realistic data sample, full of competing signals and background noise. This augmentation keeps the model on its toes, forcing it to learn the underlying patterns rather than memorizing what clear signals look like.

Results

Without getting too much into the weeds (you can read the full technical report on my GitHub Repo), I ended up training a model that was comprised of four ResNets of various depths, each of which was trained with slighlty different data augmentation regimes. The performance of this ensemble was notably better than the performance of any single counterpart.

What’s more, the performance as compared with BirdNET was also better. BirdNET was able to discover 75% of the known signals in the dataset, with a precision of 1%, meaning that for each positive detection, around 100 false positives needed to be sorted. RailNET was able to discover 75% of the signals with a precision of 5-6%, which while still poor, is a 5-fold decrease in the number of false positives. For context, in the actual survey these models were used in, the difference was roughly 7,400 false positives from BirdNET as compared with roughly 1,400 false positives from RailNET.

It is also important to note that this above result reflects BirdNET operating at it’s highest sensitivity threshold, meaning that all potential detections from BirdNET had to be reviewed to get this result. RailNET’s threshold still had plenty of room, and by dropping it to a level where it’s precision also dropped to 1%, numerous more signals were discovered. In rare signal detection, sensitivity–or the model’s ability to actually find the signals it is looking –for is of utmost importance.

RailNET was able to operate at significantly higher sensitivities while maintaining the same precision as BirdNET.

Discussion

While the precision of both models remains pretty awful in general–and there is plenty of room for improvement–this is largely due to the challenging nature of the task. The models were trained with a set of focal recordings, but their ultimate use-case is the classification of long, unbounded soundscapes that will be massively imbalanced. Class imbalance and generalization to real world data are exceedingly difficult problems to address in ML.

For context, one of my projects collected over 1,000 hours of audio. When you convert that into three-second segments, the model is ingesting and attempting to classify 1.2 million audio samples! Its first magic trick is to turn that pile of 1.2 million potential target signals into a pile of 7,000 potential target signals. This is a big number still, but with scripted processes to help, it is entirely viable to manually validate (I know, because I do it all the time!). Then, how well it can discern and assign confidence scores to these 7,000 samples is its next magic trick, because this gives you the ability to approach the task starting with the most likely signals first.

Since the lessons learned here can be applied to any species with rare, sporadic vocalizations, I plan on continuing to develop RailNET, ultimatley hoping to create an easy to execute workflow for other researchers to train models for elusive species of their choice.